The Perpetual Challenge

Understanding Transformation Through Technology, Systems, and Human Behaviour

Foreword

This is written in a more formal style than my usual as it was intended for a publication (didn’t happen) and I’ve tightened it up using Claude (disclosure)

Introduction

The landscape of technological transformation has evolved dramatically since the early 1990s, yet certain fundamental patterns persist across decades of change. Having witnessed multiple waves of technological revolution, from the commercialisation of the Internet to the current artificial intelligence revolution, one begins to recognise the cyclical nature of organisational and societal transformation challenges. This chapter examines three enduring issues that consistently emerge across transformation initiatives: human behaviour, financial imperatives, and systemic resistance to change. Drawing from extensive experience in technology transformation, particularly within the UK railway sector, this analysis explores how these interconnected factors shape our ability to navigate fundamental change in an increasingly connected world.

The transition from analogue to digital systems in the 1990s marked a pivotal moment in business transformation. For example, during this period, personal computer adoption in American households doubled from 15% to over 30%, whilst the World Wide Web evolved from a scientific tool at CERN into a commercial platform that would fundamentally alter global commerce. Yet despite these technological advances, the underlying human and systemic challenges remained remarkably consistent. Understanding these patterns becomes crucial as we stand on the precipice of another transformational wave, the integration of artificial intelligence into every aspect of organisational life. I lived through that and i’m living through the AI changes. in fact it feels that since I started working with tech in around 1990 there has been ever increasing waves of change, each getting larger and occurring every 3 - 5 years.

The railway industry (where my current day job is) provides a particularly illuminating case study for transformation challenges, representing a sector where engineering excellence must be balanced with technological innovation whilst managing complex stakeholder relationships and regulatory frameworks, wrapped in the pressures of the logistics of moving millions of people and millions of tons of freight. As digital technologies promise to deliver major performance improvements through intelligent signalling, advanced analytics, and automation, the industry faces the same fundamental trinity of challenges that have persisted throughout technological history.

The Evolution of Technological Transformation

The trajectory of technological transformation since the early 1990s reveals distinct waves of change, each building upon previous innovations whilst introducing new complexities. The commercialisation of the Internet in 1993 (the web) marked a watershed moment when several technological factors converged to unleash what would become the foundation of our current digital economy. During this period, the percentage of businesses utilising computer networks increased exponentially, driven by the realisation that information technology was becoming the nervous system of modern enterprise.

The first wave involved digitising existing analogue processes, transforming paper-based systems into computational formats, replacing physical filing systems with electronic databases, and introducing email as a replacement for traditional correspondence. This phase represented what scholars term "paving the cow path", applying new technology to existing processes without fundamentally reimagining how work should be conducted. The focus remained on efficiency gains rather than transformational change, with organisations seeking to reduce costs whilst maintaining familiar operational structures.

The second wave introduced more sophisticated integration, replacing telephone systems with device-based video calling and creating interconnected digital ecosystems. This period witnessed the emergence of what Bill Gates termed the "digital nervous system", the integration of all organisational systems and processes under common technological frameworks. Companies began recognising that technology was not merely a tool for efficiency but the foundation upon which competitive advantage would be built.

The current third wave represents a fundamental shift towards artificial intelligence and machine learning systems that can make autonomous decisions, negotiate agreements, and manage complex stakeholder relationships without direct human intervention. This evolution promises to transform not just how work is conducted, but whether traditional concepts of work remain relevant in their current form. The progression from digitisation to automation to artificial intelligence represents an acceleration that challenges our fundamental assumptions about human agency in organisational systems.

Research into digital transformation reveals that organisations implementing comprehensive change management strategies are up to seven times more likely to meet their objectives. However, the railway sector demonstrates that technical capability alone is insufficient for successful transformation. The industry's experience with digital signalling implementation shows that approximately 60% of signalling systems require renewal, yet progress remains constrained by regulatory frameworks, stakeholder resistance, and the complexity of managing change across multiple organisational boundaries.

The Internet of Things (IoT) has also emerged as a critical component of this transformation, creating what researchers describe as the "nervous system of modern enterprises". In railway applications, connected sensors monitor equipment in real-time, enabling predictive maintenance and reducing operational downtime whilst improving safety outcomes. This technological capability represents a shift from reactive to proactive management, yet implementation success depends heavily on organisational readiness for change rather than technical sophistication alone.

The Eternal Trinity: Behaviour, Money, and Systems

Three fundamental issues persistently emerge across transformation initiatives, forming an interconnected triangle of challenges that organisations must navigate regardless of technological sophistication: human behaviour, financial imperatives, and systemic resistance to change. These factors operate in complex feedback loops, where changes in one domain inevitably affect the others, creating either virtuous cycles of successful transformation or reinforcing patterns of resistance and failure.

Human Behaviour: The Psychological Foundations of Resistance

Human behaviour in organisational change contexts is driven by deeply rooted psychological mechanisms that have evolved over millennia. Research demonstrates that resistance to change is not merely stubbornness or negativity, but a complex psychological response rooted in fundamental human needs for control, predictability, and security. When transformation initiatives disrupt established routines and processes, they trigger what psychologists term the "threat response system," leading to heightened stress and a desire to retreat to familiar patterns.

The loss of control and predictability represents perhaps the most significant behavioural challenge in transformation initiatives. Employees experiencing change often perceive threats to their autonomy and ability to navigate their work environment effectively. This psychological impact stems from the disruption of cognitive frameworks that individuals use to make sense of their professional world. Fear of the unknown amplifies these responses, particularly when transformation involves job role changes, new technological requirements, or organisational restructuring.

Cognitive dissonance emerges when new systems or processes conflict with established beliefs about effective work practices. This psychological phenomenon creates internal tension that individuals resolve either by adapting to new realities or by rejecting the validity of change initiatives. Research indicates that individuals with higher tolerance for ambiguity and stronger self-efficacy beliefs are more likely to embrace organisational change, whilst those with rigid cognitive styles tend to exhibit stronger resistance patterns.

The railway sector exemplifies these behavioural challenges, where safety-critical operations have historically relied on established procedures, learned practices and hierarchical decision-making structures. Introducing AI and ML technologies requires not only learning new technical skills but fundamentally reimagining how safety, efficiency, and reliability are achieved. Staff members who have developed expertise in traditional signalling systems may perceive digital transformation as diminishing their professional value whilst introducing unacceptable safety risks.

Organisational justice emerges as a critical factor in managing behavioural resistance. When employees perceive transformation processes as fair, transparent, and respectful of their contributions, resistance decreases significantly. Conversely, top-down change initiatives that fail to acknowledge existing expertise or provide adequate support for skill development tend to generate sustained opposition that can undermine even technically sound transformation strategies.

Financial Imperatives: The Economics of Transformation

Financial considerations represent the second vertex of the transformation triangle, operating according to patterns that have remained remarkably consistent across different technological eras. Organisations typically invest in transformation only when financial benefits become demonstrably clear, treating technology as an overhead expense rather than strategic necessity until competitive pressures force recognition of its fundamental importance.

The economic history of the United Kingdom demonstrates this pattern across multiple industrial revolutions. During the First Industrial Revolution, British entrepreneurs pioneered technological innovations only when economic incentives aligned with technical possibilities (see the history of the Stockton to Darlington railway). The transition from manual labour to machine-based manufacturing occurred not because technology was available, but because market conditions made mechanisation financially advantageous. Similarly, contemporary organisations adopt digital technologies when cost structures, competitive pressures, or regulatory requirements make transformation economically inevitable.

Government estimates suggest that artificial intelligence could deliver £40 billion plus, annually in public sector productivity improvements, representing £200 billion over a five-year forecast period. However, realising these benefits requires substantial upfront investment in infrastructure, training, and organisational restructuring. The paradox of transformation economics lies in the necessity of spending money to save money, whilst demonstrating value before full implementation occurs.

Railway transformation economics exemplify this challenge. Digital signalling systems promise to increase capacity without major infrastructure interventions, potentially delivering significant cost savings over traditional approaches. However, implementation requires coordinated investment across multiple train operators, infrastructure providers, and regulatory bodies, each with different financial incentives and risk tolerance levels. The complexity of apportioning costs and benefits across organisational boundaries creates financial coordination challenges that can delay or derail technically feasible improvements.

Research indicates that organisations with effective change management practices are more likely to achieve financial objectives, stay within budget constraints, and deliver anticipated returns on transformation investments. However, financial metrics alone prove insufficient for evaluating transformation success, as they fail to capture the full range of organisational and societal benefits that emerge from systemic change initiatives.

Systems: The Institutional Architecture of Resistance

Systemic resistance represents perhaps the most intractable element of the transformation trinity, as it encompasses governance structures, institutional arrangements, and political systems that have evolved over extended periods. Stafford Beer's principle that "the purpose of a system is what it does" (POSIWID) provides crucial insight into why existing institutional arrangements resist transformation even when change would deliver superior outcomes.

The UK governmental system exemplifies this systemic challenge. Current institutional arrangements evolved over centuries, shaped by the Enlightenment emphasis on rational governance and the emergence of capitalism as an organising economic principle. These systems served imperial administration and post-industrial revolution society effectively, but their fundamental architecture reflects the technological and social realities of earlier eras rather than current transformation requirements.

Systemic resistance operates through multiple mechanisms. Established governance structures create path dependencies that make certain types of change easier to implement than others. Institutional arrangements that distribute power and resources according to existing technological capabilities may actively resist innovations that would redistribute influence or require new competencies. Professional networks, regulatory frameworks, and organisational hierarchies represent interlocking systems that reinforce existing approaches whilst creating barriers to fundamental change.

The challenge becomes particularly acute when transformation requires coordination across multiple institutional boundaries. Railway digitalisation involves coordination between train operating companies, infrastructure providers, regulatory bodies, technology suppliers, and government agencies, each operating according to different institutional logics and incentive structures. Successfully implementing digital transformation requires either aligning these diverse institutional interests or creating new governance arrangements that transcend existing organisational boundaries.

Beer's cybernetic approach suggests that viable systems must match the complexity of their environment through appropriate variety management. When external environments become more complex, as occurs during periods of rapid technological change, internal systems must either increase their complexity or develop new mechanisms for reducing environmental complexity to manageable levels. Failure to achieve this balance results in system failure or transformation failure, regardless of technical capabilities or financial resources. Getting the right systems in place is essential.

To make AI flourish, the systems currently in place will need uprooting and changing. What we have now is what those systems produce. POSIWID. Its no good relying on existing structures and expecting novelty. Add the layers of emergent Complexity to this and its easy to see that we need new structures, new processes and new behaviours if we are get the most form these new intelligent technologies.

Unlike the previous tech transformations, we are changing the very fabric of business, ops, commerce and behaviour and we don’t know what will be on the other side waiting for us. To get this new rosebush to grow well, we need top rprune right back.

Technology as the Digital Nervous System

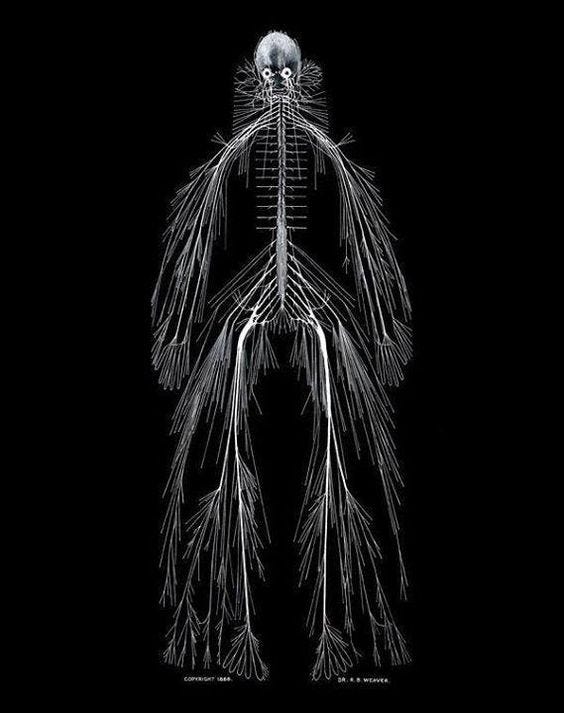

There is an oft quoted meme out there that says the human body is just a nervous system that has a structure to help it move and wears a flesh space suit to protect it form the environment. There is a great deal of truth in this. But it represents a whole new way of looking at things. the AI revolution requires exactly the same change to the way we think.

The conceptualisation of technology as an organisational nervous system, connnected to other networks, represents a fundamental shift in understanding business transformation. This metaphor transcends traditional views of technology as mere tools or support systems, positioning digital infrastructure as the sensory and communication network that enables organisational consciousness and coordinated response to environmental changes. Like biological nervous systems, technological infrastructure must integrate sensory input, process information, coordinate responses, and maintain system-wide coherence whilst adapting to changing conditions.

Modern enterprises operate as complex adaptive systems where technology provides the connective tissue linking operational activities, strategic decision-making, and stakeholder interactions. IoT sensors, data analytics platforms, artificial intelligence algorithms, and communication networks create a pervasive technological environment that monitors organisational performance, identifies emerging patterns, and enables rapid response to both opportunities and threats. This digital nervous system processes vast quantities of information in real-time, filtering relevant signals whilst maintaining overall system stability.

The railway industry demonstrates both the potential and challenges of implementing comprehensive digital nervous systems. Modern rail networks generate enormous quantities of data through train positioning systems, passenger information platforms, maintenance monitoring, and operational control systems. Digital twins technology enables the creation of virtual replicas of physical assets, allowing real-time monitoring, analysis, and optimisation of complex railway operations. When properly integrated, these technological capabilities can reduce delays, improve safety outcomes, and increase capacity without requiring major infrastructure investments.

However, developing effective digital nervous systems requires more than technological sophistication. Successful implementation depends on organisational capacity to interpret and respond to the information provided by technological systems. Human operators must develop new competencies for working with artificial intelligence tools, whilst organisational structures must evolve to support data-driven decision-making processes. The challenge lies not in collecting information but in developing organisational intelligence capable of translating data into effective action.

Research indicates that organisations successfully implementing digital nervous systems focus on cultural transformation alongside technological deployment. They invest in training programmes that help employees understand how to work effectively with intelligent systems, develop new metrics for evaluating performance in data-rich environments, and create governance arrangements that balance automated decision-making with human oversight. The most successful transformations treat technology and human capability development as complementary rather than competing priorities.

The Coming Age of Artificial Intelligence

Artificial intelligence represents a qualitatively different type of transformation compared to previous technological waves. Whilst earlier innovations primarily automated routine tasks or improved information processing capabilities, AI systems demonstrate emergent behaviours that can surpass human cognitive performance in specific domains. This shift introduces fundamental questions about human agency, decision-making authority, and the future structure of work itself.

Current AI implementations in government and business contexts already demonstrate significant productivity improvements. Teachers using AI tools for lesson planning and marking report time savings of approximately 25%, equivalent to eliminating unpaid overtime requirements. Government departments implementing intelligent automation have processed over 19 million transactions, saving more than 2 million working hours and £54 million in operational costs. These early implementations suggest that AI can enhance human capability rather than simply replacing human workers.

However, the trajectory towards more sophisticated AI systems raises profound questions about organisational control and human autonomy. As AI systems become capable of conducting negotiations, making complex decisions, and managing stakeholder relationships without direct human supervision, traditional concepts of management and oversight require fundamental reconsideration. The prospect of "distant alien intelligences" making decisions about human welfare based on algorithmic interpretations of needs and preferences challenges existing democratic and organisational governance models. These are not distant gods on hillsides.

Railway transformation provides concrete examples of both AI opportunities and challenges. Predictive maintenance systems can analyse equipment performance data to prevent failures before they occur, whilst intelligent traffic management can optimise train scheduling across complex network configurations. AI-powered passenger information systems can provide personalised journey recommendations and real-time updates that improve customer experience whilst reducing operational disruption. AI has the potential to intelligently manage and anticipate, a customer experience from conception of desire to travel to completion of journey at home. It could also manage most central operational systems.

Yet implementing AI in safety-critical environments like railways requires addressing questions of accountability, transparency, and fail-safe operation that current AI technologies struggle to satisfy completely. When AI systems make decisions that affect passenger safety or operational integrity, human operators must retain ultimate responsibility whilst working with tools whose decision-making processes may be opaque or difficult to understand.

The challenge for organisations lies in developing governance frameworks that harness AI capabilities whilst maintaining human agency and democratic accountability. This requires creating new forms of human-AI collaboration that combine algorithmic processing power with human judgment, values, and oversight capabilities. Success depends on treating AI as a powerful tool for human empowerment rather than a replacement for human decision-making.

Ask yourself, are the structures and bodies that manage the industry now really the right bodies to do that in the coming era?

Beyond Existing Systems: The Need for Fundamental Redesign

The accelerating pace of technological change demands reconsideration of fundamental institutional arrangements rather than incremental adaptation of existing systems. Traditional governance structures, organisational hierarchies, and regulatory frameworks were designed for technological and social contexts that no longer exist. Attempting to implement transformational change through existing institutional arrangements often results in suboptimal outcomes that fail to realise the full potential of new technological capabilities.

The principle that "the purpose of a system is what it does" provides crucial insight into why existing systems resist transformation. Current institutional arrangements produce the outcomes they were designed to achieve, even when those outcomes no longer align with contemporary needs or possibilities. Educational systems that prepare students for industrial-era employment may actively resist changes that would better prepare them for AI-augmented work environments. Financial systems designed around scarcity-based resource allocation may struggle to adapt to abundance-enabled by technological productivity improvements.

Cybernetic theory suggests that viable systems must continuously adapt their internal complexity to match environmental demands. When environmental complexity increases rapidly, as occurs during technological revolutions, existing systems face fundamental viability challenges that cannot be resolved through minor adjustments. Instead, they require what Beer termed "variety engineering", systematic redesign of organisational structures to handle new levels of environmental complexity.

The UK railway transformation illustrates these challenges at a practical level. Implementing digital railway capabilities requires coordination across multiple train operating companies, infrastructure providers, and regulatory bodies, each operating according to different organisational logics and incentive structures. Current institutional arrangements were designed for a railway system based on mechanical signalling, geographic service territories, and hierarchical operational control. Digital transformation requires new forms of network coordination, data sharing, and collaborative decision-making that transcend traditional organisational boundaries.

Creating systems with transformation "in their DNA" requires starting with desired outcomes and working backwards to design institutional arrangements that can achieve those outcomes. Rather than asking how existing bodies can implement AI transformation, the fundamental question becomes what institutional arrangements would best support AI-augmented human flourishing. This approach might lead to entirely new organisational forms, governance structures, and accountability mechanisms that bear little resemblance to current arrangements.

The resistance to such fundamental redesign is predictable and understandable. People whose careers, expertise, and identity are invested in existing systems naturally resist changes that might diminish their influence or require developing new competencies. However, incremental adaptation of systems designed for different technological contexts often produces suboptimal outcomes that satisfy no one whilst failing to realise transformation potential.

Conclusion

The persistent challenges of behaviour, money, and systems that have characterised technological transformation since the early 1990s continue to shape our current AI revolution. Understanding these patterns provides crucial insight into why some transformation initiatives succeed whilst others fail, despite equivalent technological sophistication or financial resources. Success depends not on overcoming these challenges but on designing transformation approaches that work with rather than against fundamental human and systemic realities.

The railway industry's experience with digital transformation demonstrates that technical feasibility alone is insufficient for achieving transformation objectives. Success requires addressing behavioural concerns through inclusive change management, aligning financial incentives across organisational boundaries, and sometimes creating entirely new institutional arrangements rather than adapting existing ones. Most importantly, it requires recognising that transformation is fundamentally about human empowerment rather than technological deployment.

As we enter the age of artificial intelligence, the stakes of getting transformation right become even higher. The technologies we are implementing have the potential to either enhance human agency and democratic governance or concentrate power in ways that diminish human autonomy. The choices we make about institutional design, governance arrangements, and human-AI collaboration will shape society for generations to come. Understanding the eternal trinity of transformation challenges provides essential foundation for making those choices wisely, ensuring that technological capability serves human flourishing rather than constraining it.

This is revolutionary on a scale not seen since we moved into cities from being hunter gatherers. Back then we invented writing, accounting, maths, and law. What will we need to invent this time?